Several months back I put out a call, asking what people would like to learn about the Python Software Foundation in my talk at PyCon. I got a lot of responses, both in email and twitter.

My favorite was from David Beazley:

I followed this advice and spent time watching a number of Samuel Beckett plays. I saw one that I particularly remember - a Python-themed version of Waiting for Godot called Waiting for 2.8. I hate to spoil it for anyone who hasn't seen it, but 2.8 never appears.

I also got a lot of requests to talk about the PSF, like this one from Nick:

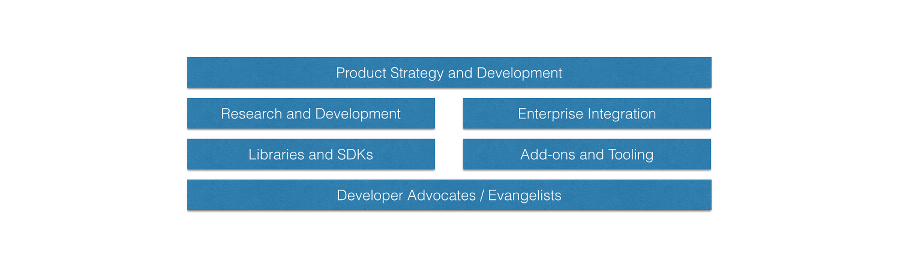

So the first thing is to explain exactly what the PSF does. This is easiest to explain by comparing the Python Community to a corporation. When most people think about the parts of the Python community, they think about it like this:

We of course have Product Strategy and Development - that is Python core dev. We also have R&D in places like PyPy and Numba. We have Enterprise Integration - Jython and IronPython. We also have libraries and SDKs, Addons, and Tooling - packages on PyPI, Anaconda, the SciPy stack, etc. We also have many developer advocates and evangelists all over the world.

In a corporate world, almost everything above is capitalizeable. That's a long way of saying that the people above this line build stuff that is valuable over a long period of time.

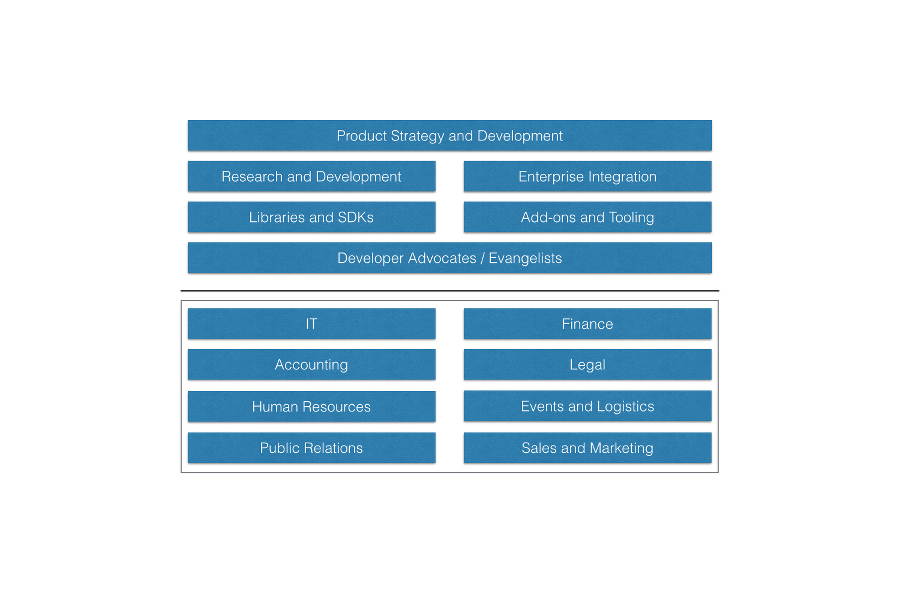

There are a bunch of other support functions, though, that support the efforts above. It is mostly what is known as G & A, or "General and Administrative Expense." The PSF takes care of this stuff. And as a general rule, these are the groups that people love to hate:

You all know these groups. IT. Finance. Accounting. Legal. Human Resources. Events and Logistics. Public Relations. Sales and Marketing. The PSF has a significant effort in all of these areas and more. We provide the support functions for many hundreds of thousands of Python users worldwide.

Some of that support is in keeping the infrastructure running - like the infrastructure that hosts PyPI, the mailing lists, and python.org. If you deploy Python infrastructure, the PSF helps you.

Some of that support is financial. We directly supported conferences where over 50,000 Python users attended. We sponsored projects and development efforts. We paid for sprints and meetups. If you attended a Python or Python-related conference, chances are that the PSF helped you.

Some of that support is legal. Not only does the PSF handle the IP associated with the cPython and Jython interpreters, we also manage trademark usage requests for "Python," the two-snakes logo, "PyCon," "PyLadies," and more. To the extent that there is a clear public perception of what "Python" is, the PSF helped with that too.

The PSF also created the PSF Code of Conduct, and actively encourages the community to be welcoming and helpful. For example, we don't fund conferences without a code of conduct. That is one reason why it is very unusual to find a conference in the Python ecosystem that doesn't have one.

We field inquiries from the press. We work out payment issues (including international ones) for companies. We keep the books straight and the lights on.

So what are the problems? There are a number of them. We're not perfect. This is supposed to be no holds barred look at what the PSF does, so I will tell you what some of the key problem areas are, and what you can do about them.

Time

The first problem is simply time. The PSF has exactly one full-time employee and three part-time employees. Everyone else at the PSF, and those who are working on PSF events like PyCon, do so as a service to the community. Even those few people who are employees serve far more than they would if this were just a job.

Now I am not complaining about this.

On a concrete level, though, people working on PSF things are limited. There are more things that we would like to do - and there are even some people who have stepped up to help. But communicating and managing and teaching takes time. It is difficult to do all those things and still have time to get the immediate items done.

So what can you do?

First, say thanks. If you see someone helping out at a conference, buy them a beverage. Recognize others for what they do. Find someone who has written a library that you can't live without and tell them what their work has done for you. You can do that via email or social media.

Second, the best thing that you can individually do to help the Python community is to reach out, lift, and mentor others. There are always new people. It doesn't matter if they are new to Python, or new to your meetup, or new to your mailing list. Welcome them in and show them the ropes. Bonus points if you bring in someone who doesn't look like you.

Third, for those who are trying to work with others in the PSF, we need you to persevere and be understanding. I heard the story of a new contributor who felt turned off because it was hard to contribute. No one was mean, but no one made the time to help someone new come in. Thankfully, she persevered and was able to land some code. She got over the hump.

There shouldn't be a hump to get over before people can contribute. But there is. Please persevere.

Empathy

The second major challenge is empathy. A lack of empathy is the biggest strategic weakness in the Python community. By empathy I mean a willingness to place yourself in another's shoes and try to see the world through their eyes.

I believe that the PSF is better at this than most open source communities. I am regularly impressed with the wonderful people in the Python community that go out of their way to help others. Nevertheless, this is still a weakness.

A lack of empathy is expressed through being dismissive of others and their point of view. It doesn't matter if you agree or not. It doesn't matter if that person is wrong. It matters if you try to understand that person and their viewpoint from the perspective of their lived experience.

This is one of my favorite quotes. As I think of it, every person is the hero of their own story. They are trying the best they can and doing good. It is a failure on our part if we dismiss people as wrong without taking the time to understand why they think they are right, or why they think their contribution is valuable.

Yes, there are trolls. But they are one out of 100, or one out of a thousand. We should eject those who are intentionally or persistently abusive.

There are a few people in every community I am in that I pretty much never agree with. But behind those few people are many others who think the same way. When I take the time to understand, I do better. Sometimes I am convinced. A lot of times not. But those people who think that I am doing it wrong teach me more than all of those who agree with me.

What can you do?

Stop labeling. Wait before you attach labels to people, or conduct, or arguments that don't take into account the content and intent of what people are saying. It's ok to have those labels - they are meaningful to you. But if you want to connect with a person, you need to reach out and start from where they are, not from where you are.

Always give people the benefit of the doubt. One of the difficult things about our society is that more and more of our discussions come through as pixels, not people. It is easy to misunderstand a statement posted on the Internet or sent through and email if you don't have the cultural and personal context that drove that statement.

This doesn't excuse things when people get hurt. As @jacobian correctly pointed out to me, intent isn't magic. But we should always, always assume that people are trying to do good and strive to understand others in that light.

Responsibility

The third biggest problem we deal with in the PSF is a lack of responsibility.

We have many people who are willing to criticize how something is done. Many of those criticisms are correct. And, truth be told, I find great value in being told when I am doing something wrong.

But.

Too many of us stop when we have raised our voice to complain, without taking responsibility to take the next step. At minimum spend the time to work out and politely express what could be done better, or even step up and help. Does this mean that if you don't like a library you need to become a core maintainer? Of course not. But it does mean that we need to take responsibility for the burdens that we ask others to take for us.

There was a thread recently where a long-time and prolific contributor described how people would insist on changes to his libraries. Users felt entitled to criticize and insist that work be done on their behalf with no thought for how that would fit within that developer's other demands.

This is not good enough. It is a failure of empathy and responsibility. It is not kind, and it needs to stop.

So what can you do?

Stop before you complain, directly to a person or generally on the Internet. Do your homework. Remember, people are always trying to do their best. Was there a problem that prevented the result you want? Find out first.

Second, look for ways that you can engage constructively. Do that instead.

Be specific and constructive. Do you still think that you should speak out? Isolate the change that needs to be made so that your feedback is actionable. "It doesn't work" isn't a bug report and "It sucks" isn't a feature request.

The next question asked what advice I might have for open source projects that want to grow up to be the PSF:

Don't rush it. You can and should set rules of the road and expectations early on, but make processes as lightweight and informal as possible.

Default to openness - but realize openness is not really an end in itself. Openness is the start of communication. What you really want to do is to understand and empower, not just check a box.

Culture matters. Build one that reflects the best of who you are. The best determinant of which technology will succeed is not the technology itself, but instead the strength and vitality of the community around it. If you put obstacles in the path of people participating with you, you put obstacles in the path of your own success.

There have been anomalies - technologies or projects that have succeeded despite a difficult or toxic culture. The time when projects or companies can succeed with toxic cultures is quickly disappearing into the rear-view mirror.

In the PSF, what we consciously try to encourage is a culture of service.

I'm going to go out on a limb because I know there are a number of people who disagree with me here. I believe that the culture of service is what sets the Python community apart from almost every other community I know. The PSF doesn't pay its directors or committee members. While we PyCon doesn't pay speakers or organizers for their service.

Don't mistake me. I am not saying that people should never be paid when they provide valuable services. I think it is wrong when commercial interests see communities as the equivalent of contractors that they don't have to pay. I also think it is reasonable to have paid positions that help empower others.

But a group where everyone only interacts if they are paid is not a community. It is a bunch of mercenaries.

A community that reaches out to serve and to help others becomes deeper, richer, and better over time. This is the reason why we reach out to others. This is why the PSF cares so much about including others, because they are our friends - or at least we hope they soon will be. Reach out and serve another person and you will find a friend.

Threats and opportunities

I got a final question via email - what are the greatest threats to Python and the Python community? What are our greatest opportunities?

In my opinion, the greatest threat to the Python community is that we are not adapting to changes in the industry fast enough. I am worried about technical shortcomings that lead people to choose other technologies, even if they would prefer to be in Python.

I don't think that other languages must "lose" for Python to win. But every time someone says, "I love Python, but I had to do my new project in ______," I get a little worried. Software is an ecosystem, and when our ecosystem shrinks, the opportunities available for all of us get diminished.

The term “software ecosystem” was coined about ten years ago in a book written by David G. Messerschmitt and Clemens Szyperski. In this book, they laid an extended argument that different people and companies, acting with their own interests in mind, can be thought about as an ecosystem just like the natural ecosystems around us. The term stuck. Even though the specific roles that Messerschmitt and Szyperski imagined haven’t caught on, the concept has. For example, Stephen O’Grady from the analyst firm RedMonk named his blog “tecosystems" after this concept, "because," as he says, "technology is just another ecosystem."

Python has a huge and vibrant ecosystem. Everyone in the Python community is a beneficiary of this fact. But Python has lost something in the transition: underdog status.

It was ten years ago that Paul Graham wrote “The Python Paradox,” in which he said:

"[P]eople don't learn Python because it will get them a job; they learn it because they genuinely like to program and aren't satisfied with the languages they already know.

Which makes them exactly the kind of programmers companies should want to hire. Hence what, for lack of a better name, I'll call the Python paradox: if a company chooses to write its software in a comparatively esoteric language, they'll be able to hire better programmers, because they'll attract only those who cared enough to learn it. And for programmers the paradox is even more pronounced: the language to learn, if you want to get a good job, is a language that people don't learn merely to get a job.”

Isn’t it funny that ten years ago Python was considered “relatively esoteric”? This is the most recent ranking of programming languages based on a cross-tabulation of github projects and stack overflow questions. Python comes in a solid #3. In other publications, Python is a solid top-4 or top-5 language, and is considered a “safe and well-supported” choice by publications like CTO magazine.

Why does underdog status matter? Because in 2015, there is no more Python paradox. A number of key developer communities have moved on, setting the stage for Python to be disrupted (in an Innovator's Dilemma sense). I may talk a lot about improving our community, but I think the Python community is our greatest strength. Our weakness, right now, is technical.

From a technical perspective, three threats I worry about most, and they are all related: multicore, mobile, and package management. From a language standpoint, I am really worried about Javascript and Go.

The reasons Javascript worries me should be broadly apparent. It is the most widely deployed language on the planet except for C and C++. It is dynamic, it is getting lots of funding, and it is an intrinsic part of the web.

As for Go, that is a more fundamental threat. Go is close to the metal, has an easy-to-understand concurrency model, is mostly low friction, and is "close enough" to good that it is becoming a language of choice for networked applications. It also has a deployment story that is way better than it is for Python: Copy the binary and it's done!

Go also has the advantage that it has full-time developers working on nothing but improving Go. Twenty years on, and we still don't have full-time developers working on Python. Every core dev in Python is contributing "on the side."

The problem with Go is that any code written in Go is dead code. Because of the static linking, because the primary compiler uses an unusual calling convention, any effort that people put into Go software is locked into the Go ecosystem. Unlike, say, Rust, there is no way to use Go for the things that it is good at and use Python in the places where it shines. If someone makes the shift to Go, they have to go all-in. It makes the choice stark.

What is our greatest opportunity? That is easy - schoolkids. Python either is, or is becoming the dominant teaching language across the world. Organizations from middle school on up to universities are adopting Python as their teaching language.

The Raspberry Pi includes Python 3. MicroPython is incredibly successful in the embedded world. The BBC Microbit is going to be distributed to every single child in the UK - and it will be programmable in Python 3.

With so many new people being exposed to Python, we have the opportunity to create great new things. We have dedicated, wonderful people who are trying to move the world forward. If we are able to evolve so that we can address our challenges, Python has the potential to be the dominant dynamic language worldwide.